I’ve noticed something. The more senior someone is in an organisation, the more likely they are to be furthest away from the organisation’s front door. That means they are also distant from its actual activities, the workforce, and their customers (and/or product for that matter). That’s a huge own goal and missed opportunity.

The big issue, and one that forms the premise of my thinking, is your location at work. More specifically the physical location of the CEO, in relation to the workforce, and in proximity to the exchanges with customers.

CEOs seem to occupy the very top floor, in the far corner, locked away in private offices, which happens to be the greatest distance from the front door, and they sit behind a desk that is nearest the largest windows with the finest view available, basking in the best natural light the building has to offer. They are the ‘penthouse primes’.

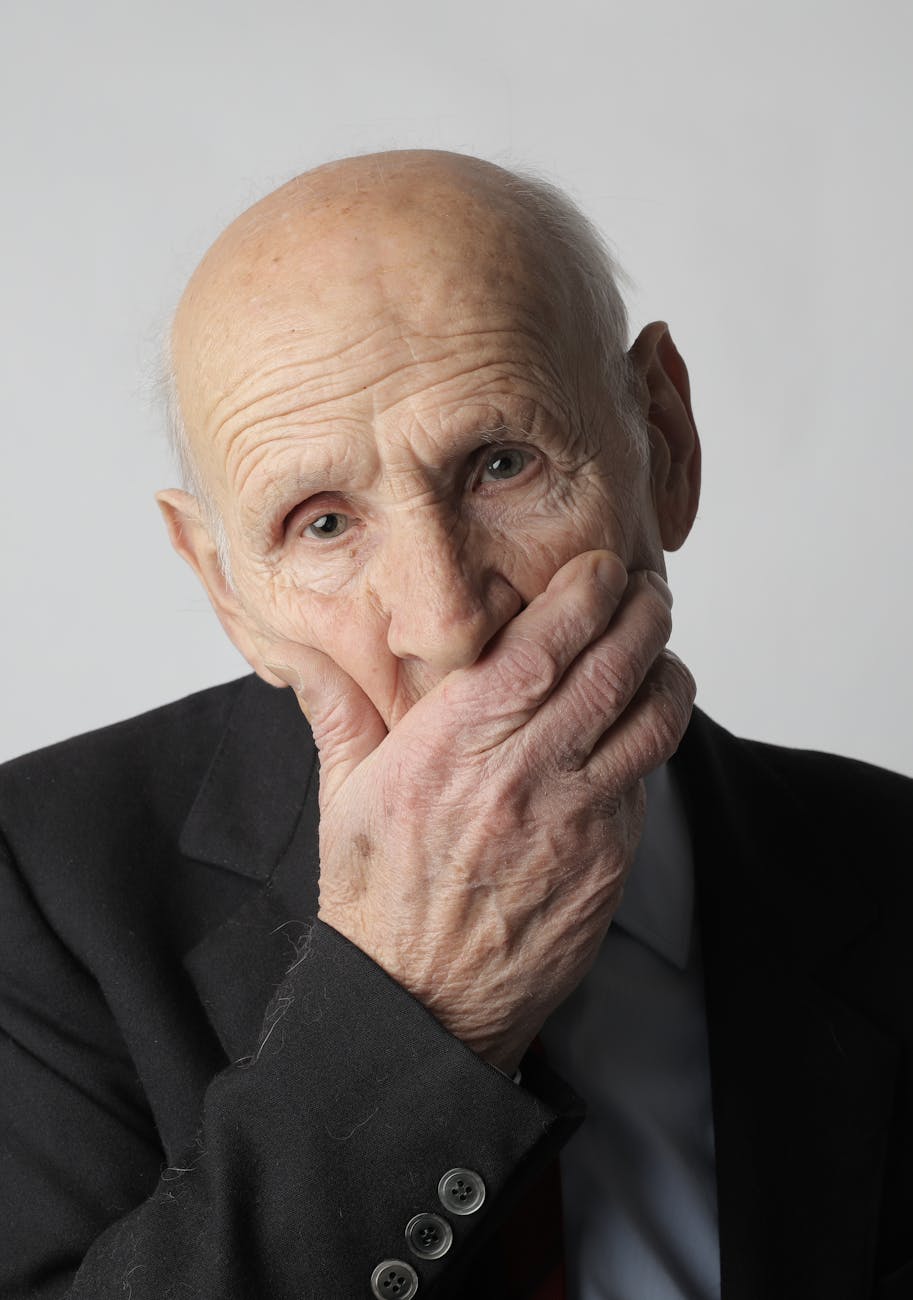

It seems to me that CEOs are not only needing to pay attention to the glass ceiling, but the glass bubble too. Their bubbles are an encapsulating and almost invisible barrier separating them from the world around them. Close to the view, but behind the glass partition that conjures up the idea of connection, but in reality is a hard and fast glass wall.

All sorts of things cause this detached situation, CEOs may argue they have lots of demands upon their time, that they need privacy or quiet spaces to have confidential discussions, and that there are too many meetings to be had. It could all be the result of delegation going too far, resulting in all such interactions being discharged by other managers or departments altogether.

It could be something that middle management is deliberately manipulating. Perhaps they are wanting the CEO to be disconnected from the realities of what is going on. They could be distancing the CEO’s place or filling the CEO’s time with unnecessary distractions and meetings, so they do not come to appreciate the failings and problems in the business, in the balance sheet, or in the market.

To hide away is one of the reactions and defences to feelings of fear. It could be the CEO is feeling afraid of interactions with staff or customers or feeling uncomfortable about conflict resolution. Some do rise to the top, never had, or have forgotten such skills. Don’t misunderstand me, the role of the CEO can be a tough one. There can be lots of problems in an organisation related to its workforce, economics, or product that are too difficult to address, and hiding away and being invisible seems like the easiest option. Especially considering the enormous risks presented by the outside world, or unexpected attention from attending a Coldplay gig. But being far away is not the best route, nor is it an effective, or fair option.